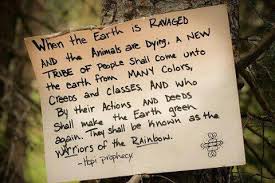

What is the Prophecy that Indigenous of Many Lands shared in Oral -Fireside Chats?

“The souls of these first people would return in bodies of all different colors: red, white, yellow and black. Together and unified, like the colors of the rainbow, these people would teach all of the peoples of the world how to have love and reverence for Mother Earth, of whose very stuff we human beings are also made.”

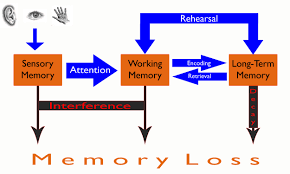

“The Elders would serve as mnemonic pegs to each other. They will be speaking individually uninterrupted in a circle one after another. When each Elder spoke they were conscious that other Elders would serve as ‘peer reviewer’ [and so] they did not delve into subject matter that would be questionable. They did joke with each other and they told stories, some true and some a bit exaggerated but in the end the result was a collective memory. This is the part which is exciting because when each Elder arrived they brought with them a piece of the knowledge puzzle. They had to reach back to the teachings of their parents, grandparents and even great-grandparents. These teachings were shared in the circle and these constituted a reconnaissance of collective memory and knowledge. In the end the Elders left with a knowledge that was built by the collectivity.”

Stephen J. Augustine

Hereditary Chief and Keptin of the Mi’kmaq Grand Council

Oral societies record and document their histories in complex and sophisticated ways, including performative practices such as dancing and drumming. Although most oral societies, Aboriginal or otherwise, have now adopted the written word as a tool for documentation, expression and communication, many still depend on oral traditions and greatly value the oral transmission of knowledge as an intrinsic aspect of their cultures and societies.

Furthermore, discussions of oral history have occasionally been framed in oversimplistic oppositional binaries: oral/writing, uncivilized/civilized, subjective/objective. Critics wary of oral history tend to frame oral history as subjective and biased, in comparison to writing’s presumed rationality and objectivity. In Western contexts, authors of written documents tend to be received automatically as authorities on their subjects and what is written down is taken as fact. Such assumptions ignore the fact that authors of written documents bring their own experiences, agendas and biases to their work—that is, they are subjective.

http://lightningmedicinecloud.com/legend.html

In the United States what are the stories?

The Native Americans see the birth of a white buffalo calf as the most significant of prophetic signs, equivalent to the weeping statues, bleeding icons, and crosses of light that are becoming prevalent within the Christian churches today. Where the Christian faithful who visit these signs see them as a renewal of God’s ongoing relationship with humanity, so do the Native Americans see the white buffalo calf as the sign to begin life’s sacred hoop.

“The arrival of the white buffalo is like the second coming of Christ,” says Floyd Hand Looks For Buffalo, an Oglala Medicine Man from Pine Ridge, South Dakota. “It will bring about purity of mind, body, and spirit and ; unify all nations—black, red, yellow, and white.” He sees the birth of a white calf as an omen because they happen in the most unexpected places and often among the poorest people in the nation. The birth of the sacred white buffalo provides those within the Native American community with a sense of hope and an indication that good times are to come.

The telling of a story from one culture to another is complex; without living in the culture, we miss much of the story’s significance. However, it can still have meaning for us if we take the time to learn about the philosophy of the culture from which it came, perhaps meditating or reflecting on its place in our own lives.

From: https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/oral_traditions/

Oral history and oral tradition

Some experts and scholars differentiate between oral history and oral tradition, but some do not. Anthropologist and historian Jan Vansina distinguishes the two as follows:11

The sources of oral historians are reminiscences, hearsay, or eyewitness accounts about events and situations which are contemporary, that is, which occurred during the lifetime of the informants. This differs from oral traditions in that oral traditions are no longer contemporary. They have passed from mouth to mouth, for a period beyond the lifetime of the informants . . .

Vansina adds that oral traditions may be “spoken, sung, or called out on musical instruments only” and although they are passed down from a generation or more ago, they are not necessarily about the past nor are they necessarily narratives.12 Vansina, however, has worked principally with oral societies in Africa. The ways in which oral societies around the world organize and understand their narratives vary.

This includes variation among First Nations’ historiographies. Stephen J. Augustine of the Mi’kmaq nation does not discern a difference between oral tradition and oral history: “When I consider the question of difference in my own Mi’kmaq language I cannot find any difference or reason why there should be a difference between oral tradition and oral history.”13 Some scholars have suggested that taking Aboriginal oral histories out of their native languages and fitting them into English terms such as legend, history, or story, and their corresponding concepts, may create artificial divisions.14 Stó:l? historian Naxaxahlts’i describes some of the different types of histories as understood by the Stó:l?. Sxwóxwiyam refers to creation stories, or, as Naxaxahlts’i puts it, “the stories about when Xexa:ls, the Transformers, travelled to our land to make the world right.” Sqwelsqwel on the other hand, refers to family history, or “the family’s truth.”15 Other Aboriginal groups have their own terminology for such narratives.

Anthropologist Bruce Miller uses the term oral narratives to encompass all of these meanings and to sidestep the oral tradition/oral history dichotomy, which he argues may present a false or overly simplistic division based on Western understandings. For Miller, by applying the term oral narratives, scholars can move beyond a superficial treatment of oral histories, and view them as both histories that are memorized and performed, and intellectual exercises of oral historiography informed by the agency of oral historians.16

Recording oral narratives

Oral history has been increasingly recognized in academia as a valuable contribution to the historical record. Interviews were and are recorded, transcribed, reread, and analyzed. Yet oral historian Alessandro Portelli cautions that the transcript is not the oral narrative and should not be seen as such. Transcription by its very nature must adhere to the rules and regulations of its written language—punctuation marks, for example, that give a sense of the way something was said but do not account for the rhythm or the melody of one’s voice or the variations in diction that emphasize different points or feelings. Portelli believes that narratives convey meaning that “can only be perceived by listening, not by reading,” and that simply reading a transcript “flattens the emotional content.”18 In addition, a written document allows no immediate feedback—there is no opportunity for dialogue or spontaneity. Audio or audiovisual recordings can present similar problems—principally, that certain contexts might not translate.

Aboriginal oral histories within a legal context

It happened at a meeting between an Indian community in northwest British Columbia and some government officials. The officials claimed the land for the government. The natives were astonished by the claim. They couldn’t understand what these relative newcomers were talking about. Finally one of the elders put what was bothering them in the form of a question. “If this is your land,” he asked, “where are your stories?

J. Edward Chamberlin, If This is Your Land, Where are Your Stories?

The use of oral histories as evidence in the court of law has become a topic of much discussion and debate in Canada. Perhaps the most famous example of oral history within a legal context is the provincial supreme court case Delgamuukw v. British Columbia. Delgamuukw was the first case in which the court accepted oral history as evidence, even though Justice Allen McEachern ended up dismissing this evidence as unreliable.

In this court case, the Gitksan and Wet’suwet’en peoples argued that they had Aboriginal title to the lands in British Columbia that make up their traditional territories. In order to prove their title, they had to provide evidence that they had occupied their territories for thousands of years. Without written documents to make their case, Gitksan and Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs presented their oral histories in the form of narratives, dances, speeches and songs.

Their testimony, however, fell on deaf ears, and while he accepted their oral history as evidence, Justice Allen McEachern concluded that it held no weight. In his now infamous ruling, he concluded that the Gitksan and Wet’suwet’en’s ancestors were a “people without culture,” who had “no written language, no horses or wheeled vehicles.”19 He even cited 17th-century philosopher Thomas Hobbes to support his views, calling the lives of the Gitksan and Wet’suwet’en’s ancestors “nasty, brutish, and short.”

The case did not end there. On appeal, the Gitskan and Wet’suwet’en won a precedent-setting victory for oral history to be given weight as legal evidence. Chief Justice Lamar of the Supreme Court of Canada concluded,

The laws of evidence must be adapted in order that [oral] evidence can be accommodated and placed on an equal footing with the types of historical evidence that courts are familiar with, which largely consists of historical documents. . . . To quote Dickson C.J., given that most aboriginal societies “did not keep written records,” the failure to do so would “impose an impossible burden of proof” on aboriginal peoples, and “render nugatory” any rights that they have (Simon v. The Queen, [1985] 2 S.C.R. 387, at p. 408). This process must be undertaken on a case-by-case basis.

After Delgamuukw, a number of court cases have further defined how to interpret oral histories as evidence in court. In Squamish Indian Band v. Canada (2001 FCT 480) and R. v. Ironeagle (2000 2 CNLR 163), the court accepted oral histories as evidence but stipulated that the weight given to oral histories must be determined in relation to how they are regarded within their own societies. In her ruling in the Squamish case, Justice Simpson also noted that she might not have given the oral histories that were presented before her much weight if she had found written records that held the same information which she could use instead. Simpson further noted that the oral histories were “sometimes contradictory.” Legal scholar Drew Mildon uses Simpson’s ruling as an example of how a judge’s “doubt and skepticism” challenges the very nature of oral history: “[Oral] evidence may be deemed inadmissible. . . . simply because there is other evidence available [to use instead]. Lastly, it is characterized as contradictory (which one assumes never happens in written history.)”20

In 2002, the Tsilhqot’in took the province of British Columbia to court to assert title to their lands. Justice David Vickers found that the oral histories presented to him by members of the Tsilhqot’in Nation were sufficient to prove their Aboriginal title. He also rejected the Crown’s claims that oral tradition was unreliable or should be measured against written documents, as it was equally impossible to determine the accuracy of historic fieldnotes or, more specifically in the Tsilhqot’in case, a 1900 ethnography on the “Chilcotin Indians.”21 More broadly, Vickers observed that “disrespect for Aboriginal people is a consistent theme in the historical documents.”22

Delgamuukw and subsequent court cases have forced Western legal systems to reconsider the validity of Aboriginal oral traditions and their continued significance and relevance in Aboriginal societies and cultures. The Canadian legal system has begun to make adjustments to incorporate this reality, though courts still struggle to fairly consider evidence that is from a different cultural context without forcing it into a Western framework. Reception to oral history in mainstream Canadian society has begun to grow too. As law professor John Borrows suggests in the title to his article on the subject, perhaps the courts as well as mainstream society are now “listening for a change.”23

By Erin Hanson.

Recommended resources

Archibald, Jo-ann (Q’um Q’um Xiiem). Indigenous Storywork: Educating the Heart, Mind, Body and Spirit. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2008.

Basso, Keith. Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language among the Western Apache. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996.

Borrows, John. “Listening for a Change: The Courts and Oral Tradition.” Osgoode Hall Law Journal 39, no. 1 (2001), 1–38.

Canada. Indian and Northern Affairs. “Oral Narratives and Aboriginal Pasts—An Interdisciplinary Review of the Literatures on Oral Traditions and Oral Histories.” http://www.ainc-inac.gc.ca/ai/rs/pubs/re/orl/orl-eng.asp

Chamberlain, J. Edward. If This is Your Land, Where are Your Stories?: Finding Common Ground. Toronto: A.A. Knopf Canada, 2003.

Cruikshank, Julie. Do Glaciers Listen?: Local Knowledge, Colonial Encounters and Social Imagination. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2005.

—- The Social Life of Stories: Narrative and Knowledge in the Yukon Territory. Vancouver: UBC Press, 1998.

—- “Oral Tradition and Oral History: Reviewing Some Issues.” Canadian Historical Review 75, no. 3 (1994): 403–18.

—- “Invention of Anthropology in British Columbia’s Supreme Court: Oral Tradition as Evidence in Delgamuukw v. B.C.”[as per BC Studies website] BC Studies 95 (Autumn 1992):25–42.

Hulan, Renée, and Renate Eigenbrod, eds. Aboriginal Oral Traditions: Theory, Practice, Ethics. Halifax: Fernwood Publishing, 2008.

Hymes, Dell. “In Vain I Tried to Tell You”: Essays in Native American Ethnopoetics. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1981.

Murray, Laura J, and Keren Rice, eds. Talking on the Page: Editing Aboriginal Texts. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999.

Napoleon, Val. “Delgamuukw: A Legal Straightjacket for Oral Histories?” Canadian Journal of Law and Society 20, no. 2 (2005): 123–55.

Ridington, Robin, and Jillian Ridington. When You Sing It Now, Just Like New: First Nations Poetics, Voices, and Representations. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006.

Tonkin, Elizabeth. Narrating Our Pasts: The Social Construction of Oral History. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs. “Oral History.” In Stolen Lands, Broken Promises: Researching the Indian Land Question (2nd ed.)Vancouver: Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs, 2005. 109-119.

Endnotes

1 Stephen J. Augustine, “Oral Histories and Oral Traditions,” in Aboriginal Oral Traditions: Theory, Practice, Ethics, ed. Renée Hulan and Renate Eigenbrod (Halifax: Fernwood Publishing, 2008), 2–3.

2 Hulan and Eigenbrod, 7.

3 Albert “Sonny” McHalsie (Naxaxalht’i), “We Have to Take Care of Everything That Belongs to Us,” in Be of Good Mind: Essays on the Coast Salish, ed. Bruce Granville Miller (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2007), 82.

4 Robert Perks and Alistair Thomson, eds., The Oral History Reader (London: Routledge, 1998), ix–xiii.

5 Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, vol. 1, Looking Forward, Looking Back (Ottawa: The Commission, 1996), 33.

6 Bruce Miller, personal correspondence with Erin Hanson, August 13, 2010.

7 John Borrows, “Listening for a Change: The Courts and Oral Tradition,” Osgoode Hall Law Journal 39, no. 1 (2001): 10.

8 Wendy C. Wickwire, “To See Ourselves as the Other’s Other: Nlaka’pamux Contact Narratives.” Canadian Historical Review 75, no. 1 (1994):19.

9 Keith Thor Carlson, ed., A Stó:l?–Coast Salish Historical Atlas (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2001), 6.

10 For in-depth explorations of the connections between landscapes, people and their oral traditions, see, for example, Keith Basso, Wisdom Sits in Places (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996); and Julie Cruikshank, Do Glaciers Listen? Local Knowledge, Colonial Encounters and Social Imagination (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2005). See our bibliography, above, for other relevant resources.

11 Jan Vansina, Oral Tradition As History (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985), 12–13.

12 Ibid.

13 Augustine, 3.

14 Drew Mildon, “A Bad Connection: First Nations’ Oral Evidence and the Listening Ear of the Courts,” in Aboriginal Oral Traditions: Theory, Practice, Ethics, 90.

15 McHalsie (Naxaxalhts’i), 92.

16 See, for example, Bruce Miller, Oral Narratives on Trial (Vancouver: UBC Press, forthcoming.)

17 Alessandro Portelli, “What Makes Oral History Different,” in The Oral History Reader, 34.

18 Ibid., 34–5.

19 Delgamuukw v. British Columbia [1997] 3 S.C.R. 1010, par. 13.

20 Ibid., par. 87.

21 Tsihlqot’in Nation v. British Columbia, 2007 BSCS 1700, par. 177, http://www.courts.gov.bc.ca/Jdb-txt/SC/07/17/2007BCSC1700.pdf

22 Ibid., par. 194.

23 Borrows.