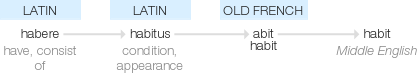

Origin

Middle English: from Old French abit, habit, from Latin habitus ‘condition, appearance’, from habere ‘have, consist of’. The term originally meant ‘dress, attire’, later coming to denote physical or mental constitution.

Habits!

What is the relationship you have with your habits?

Are they habits grounded in your principles and support your highest expression?

Or are they “bad” habits that frustrate and annoy you as you clearly see how they are holding you back?

I want to share with you what I’ve learned about letting go of habits that no longer serve you so you can adopt new habits that uplift and support your journey!

- Are you feeling physically vital?

- Is your love life juicy and stable?

- Do you have friendships that are fulling and empowering?

- Do you know your purpose and are you taking steps to make it your vocation?

- Are you financially stable and creating wealth?

- Is your spiritual life a priority and not lost in distraction?

Join me for a group coaching call so you can take a deep dive into your habits and learn how to make them work for you and not against you!

__________________________

Monthly Coaching Call with Dr. Sarah

__________________________

Exciting Announcement! Miracle Makers Academy Has a New App for Your Phone!

I have some very exciting news to share with you!

Do you know what I get asked a lot these days?

“Hey Dr. Sarah, do you have an app for Miracle Makers Academy that I can download?”

That may sound silly, but the truth is, many of my academy members want to be able to learn while they’re out and about.

Well, I have great news!

You can now get all of the Miracle Makers Academy courses, MasterClass recording, and guided meditations right on your phone!

All you need to do is head over to https://pages.kajabi.com/mobile-app-download and download the free Kajabi app.

What’s Kajabi?

It’s the platform I use to host the academy, including the Miracle Manifestation Method and the entire library of recordings.

Once you download the free Kajabi app, go ahead and sign in with the email you use for the Miracle Makers Academy, and that’s it!

With the new mobile app feature, you’ll be able to read or watch all of the academy content right from your phone. The app also automatically saves your progress, even when you switch between sessions and devices.

I’ve already been playing with it and I’m amazed at how simple and easy it is to navigate and access my academy library.

I know that all the members are going to love it!

So go ahead and download the Kajabi app and you’ll have the Miracle Makers Academy right in your pocket!

So excited for you and our growing community!

I look forward to working with you to make your dreams come true!

To your extraordinary success where ever you are on your journey!

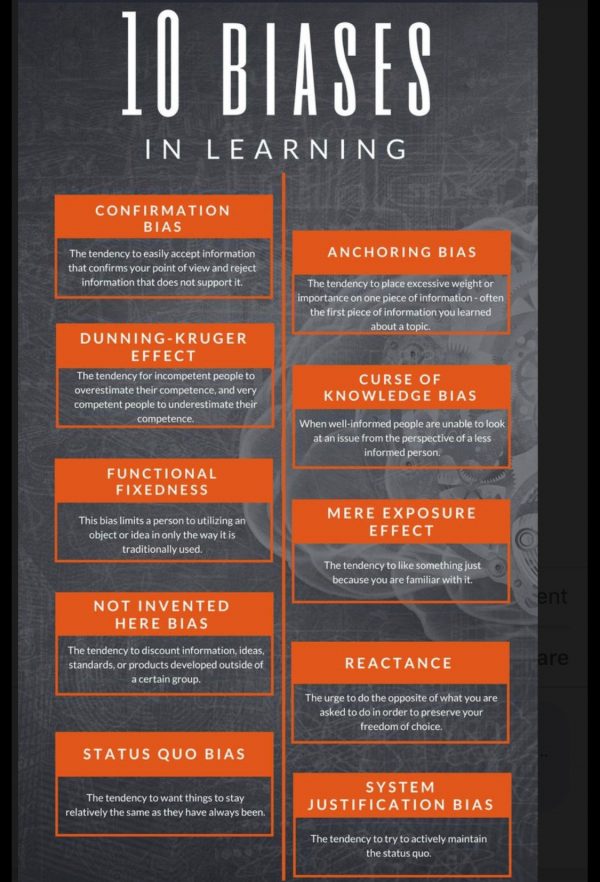

Where do your beliefs and opinions come from? If you’re like most people, you honestly believe that your convictions are rational, logical, and impartial, based on the result of years of experience and objective analysis of the information you have available. In reality, all of us are susceptible to a tricky problem known as a confirmation bias—our beliefs are often based on paying attention to the information that upholds them while at the same time tending to ignore the information that challenges them.

Understanding Confirmation Bias

A confirmation bias is a type of cognitive bias that involves favoring information that confirms your previously existing beliefs or biases.

For example, imagine that a person holds a belief that left-handed people are more creative than right-handed people. Whenever this person encounters a person that is both left-handed and creative, they place greater importance on this “evidence” that supports what they already believe. This individual might even seek “proof” that further backs up this belief while discounting examples that don’t support the idea.

Confirmation biases impact how we gather information, but they also influence how we interpret and recall information. For example, people who support or oppose a particular issue will not only seek information to support it, they will also interpret news stories in a way that upholds their existing ideas. They will also remember details in a way that reinforces these attitudes.

Confirmation Biases in Action

Consider the debate over gun control. Let’s say Sally is in support of gun control. She seeks out news stories and opinion pieces that reaffirm the need for limitations on gun ownership. When she hears stories about shootings in the media, she interprets them in a way that supports her existing beliefs.

Henry, on the other hand, is adamantly opposed to gun control. He seeks out news sources that are aligned with his position. When he comes across news stories about shootings, he interprets them in a way that supports his current point of view.

These two people have very different opinions on the same subject and their interpretations are based on their beliefs. Even if they read the same story, their bias tends to shape the way they perceive the details, further confirming their beliefs.

The Impact of Confirmation Biases

In the 1960s, cognitive psychologist Peter Cathcart Wason conducted a number of experiments known as Wason’s rule discovery task. He demonstrated that people have a tendency to seek information that confirms their existing beliefs. Unfortunately, this type of bias can prevent us from looking at situations objectively. It can also influence the decisions we make and can lead to poor or faulty choices.

During an election season, for example, people tend to seek positive information that paints their favored candidates in a good light. They will also look for information that casts the opposing candidate in a negative light.

By not seeking out objective facts, interpreting information in a way that only supports their existing beliefs, and only remembering details that uphold these beliefs, they often miss important information. These details and facts might have otherwise influenced their decision on which candidate to support.

Observations by Psychologists

In his book Research in Psychology: Methods and Design, C. James Goodwin gives a great example of confirmation bias as it applies to extrasensory perception:

“Persons believing in extrasensory perception (ESP) will keep close track of instances when they were ‘thinking about Mom, and then the phone rang and it was her!’ Yet they ignore the far more numerous times when (a) they were thinking about Mom and she didn’t call and (b) they weren’t thinking about Mom and she did call. They also fail to recognize that if they talk to Mom about every two weeks, their frequency of ‘thinking about Mom’ will increase near the end of the two-week-interval, thereby increasing the frequency of a ‘hit.'”

As Catherine A. Sanderson points out in her book Social Psychology, confirmation bias also helps form and re-confirm stereotypes we have about people.

“We also ignore information that disputes our expectations. We are more likely to remember (and repeat) stereotype-consistent information and to forget or ignore stereotype-inconsistent information, which is one way stereotypes are maintained even in the face of disconfirming evidence. If you learn that your new Canadian friend hates hockey and loves sailing, and that your new Mexican friend hates spicy foods and loves rap music, you are less likely to remember this new stereotype-inconsistent information.”

Confirmation bias is not only found in our personal beliefs, it can affect our professional endeavors as well. In the book Psychology, Peter O. Gray offers this example of how confirmation bias may affect a doctor’s diagnosis:

“Groopman (2007) points out that the confirmation bias can couple with the availability bias in producing misdiagnosis in a doctor’s office. A doctor who has jumped to a particular hypothesis as to what disease a patient has may then ask questions and look for evidence that tends to confirm that diagnosis while overlooking evidence that would tend to disconfirm it. Groopman suggests that medical training should include a course in inductive reasoning that would make new doctors aware of such biases. Awareness, he thinks, would lead to fewer diagnostic errors. A good diagnostician will test his or her initial hypothesis by searching for evidence against that hypothesis.”

A Word From Verywell

Unfortunately, we all have confirmation bias. Even if you believe you are very open-minded and only observe the facts before coming to conclusions, it’s very likely that some bias will shape your opinion in the end. It’s very difficult to combat this natural tendency.

That said, if we know about confirmation bias and accept the fact that it does exist, we can make an effort to recognize it by working to be curious about opposing views and really listening to what others have to say and why. This can help us better see issues and beliefs from another perspective, though we still need to be very conscious of wading past our confirmation bias.

The Dunning-Kruger effect is a type of cognitive bias in which people believe that they are smarter and more capable than they really are. Essentially, low ability people do not possess the skills needed to recognize their own incompetence. The combination of poor self-awareness and low cognitive ability leads them to overestimate their own capabilities.

The term lends a scientific name and explanation to a problem that many people immediately recognize—that fools are blind to their own foolishness. As Charles Darwin wrote in his book The Descent of Man, “Ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge.”

An Overview of the Dunning-Kruger Effect

This phenomenon is something you have likely experienced in real life, perhaps around the dinner table at a holiday family gathering. Throughout the course of the meal, a member of your extended family begins spouting off on a topic at length, boldly proclaiming that he is correct and that everyone else’s opinion is stupid, uninformed, and just plain wrong. It may be plainly evident to everyone in the room that this person has no idea what he is talking about, yet he prattles on, blithely oblivious to his own ignorance.

The effect is named after researchers David Dunning and Justin Kruger, the two social psychologists who first described it. In their original study on this psychological phenomenon, they performed a series of four investigations.

People who scored in the lowest percentiles on tests of grammar, humor, and logic also tended to dramatically overestimate how well they had performed (their actual test scores placed them in the 12th percentile, but they estimated that their performance placed them in the 62nd percentile).

The Research

In one experiment, for example, Dunning and Kruger asked their 65 participants to rate how funny different jokes were. Some of the participants were exceptionally poor at determining what other people would find funny—yet these same subjects described themselves as excellent judges of humor.

Incompetent people, the researchers found, are not only poor performers, they are also unable to accurately assess and recognize the quality of their own work. This is the reason why students who earn failing scores on exams sometimes feel that they deserved a much higher score. They overestimate their own knowledge and ability and are incapable of seeing the poorness of their performance.

Low performers are unable to recognize the skill and competence levels of other people, which is part of the reason why they consistently view themselves as better, more capable, and more knowledgeable than others.

“In many cases, incompetence does not leave people disoriented, perplexed, or cautious,” wrote David Dunning in an article for Pacific Standard. “Instead, the incompetent are often blessed with an inappropriate confidence, buoyed by something that feels to them like knowledge.”

This effect can have a profound impact on what people believe, the decisions they make, and the actions they take. In one study, Dunning and Ehrlinger found that women performed equally to men on a science quiz, and yet women underestimated their performance because they believed they had less scientific reasoning ability than men. The researchers also found that as a result of this belief, these women were more likely to refuse to enter a science competition.

Dunning and his colleagues have also performed experiments in which they ask respondents if they are familiar with a variety of terms related to subjects including politics, biology, physics, and geography. Along with genuine subject-relevant concepts, they interjected completely made-up terms.

In one such study, approximately 90 percent of respondents claimed that they had at least some knowledge of the made up terms. Consistent with other findings related to the Dunning-Kruger effect, the more familiar participants claimed that they were with a topic, the more likely they were to also claim they were familiar with the meaningless terms. As Dunning has suggested, the very trouble with ignorance is that it can feel just like expertise.

Causes of the Dunning-Kruger Effect

So what explains this psychological effect? Are some people simply too dense, to be blunt, to know how dim-witted they are? Dunning and Kruger suggest that this phenomenon stems from what they refer to as a “dual burden.” People are not only incompetent; their incompetence robs them of the mental ability to realize just how inept they are.

Incompetent people tend to:

- Overestimate their own skill levels

- Fail to recognize the genuine skill and expertise of other people

- Fail to recognize their own mistakes and lack of skill

Dunning has pointed out that the very knowledge and skills necessary to be good at a task are the exact same qualities that a person needs to recognize that they are not good at that task. So if a person lacks those abilities, they remain not only bad at that task, but ignorant to their own inability.

An Inability to Recognize Lack of Skill and Mistakes

Dunning suggests that deficits in skill and expertise create a two-pronged problem. First, these deficits cause people to perform poorly in the domain in which they are incompetent. Secondly, their erroneous and deficient knowledge makes them unable to recognize their mistakes.

A Lack of Metacognition

The Dunning-Kruger effect is also related to difficulties with metacognition, or the ability to step back and look at one’s own behavior and abilities from outside of oneself. People are often only able to evaluate themselves from their own limited and highly subjective point of view. From this limited perspective they seem highly skilled, knowledgeable, and superior to others. Because of this, people sometimes struggle to have a more realistic view of their own abilities.

A Little Knowledge Can Lead to Overconfidence

Another contributing factor is that sometimes a tiny bit of knowledge on a subject can lead people to mistakenly believe that they know all there is to know about it. As the old saying goes, a little bit of knowledge can be a dangerous thing. A person might have the slimmest bit of awareness about a subject, yet thanks to the Dunning-Kruger effect, believe that he or she is an expert.

Other factors that can contribute to the effect include our use of heuristics, or mental shortcuts that allow us to make decisions quickly, and our tendency to seek out patterns even where none exist. Our minds are primed to try to make sense of the disparate array of information we deal with on a daily basis. As we try to cut through the confusion and interpret our own abilities and performance within our individual worlds, it is perhaps not surprising that we sometimes fail so completely to accurately judge how well we do.

Who Is Affected by the Dunning-Kruger Effect?

So who is affected by the Dunning-Kruger effect? Unfortunately, we all are. This is because no matter how informed or experienced we are, everyone has areas in which they are uninformed and incompetent. You might be smart and skilled in many areas, but no one is an expert at everything.

The reality is that everyone is susceptible to this phenomenon, and in fact, most of us probably experience it with surprising regularity. People who are genuine experts in one area may mistakenly believe that their intelligence and knowledge carry over into other areas in which they are less familiar. A brilliant scientist, for example, might be a very poor writer. In order for the scientist to recognize their own lack of skill, they needs to possess a good working knowledge of things such as grammar and composition. Because those are lacking, the scientist in this example also lacks the ability to recognize their own poor performance.

The Dunning-Kruger effect is not synonymous with low IQ. As awareness of the term has increased, its misapplication as a synonym for “stupid” has also grown. It is, after all, easy to judge others and believe that such things simply do not apply to you.

So if the incompetent tend to think they are experts, what do genuine experts think of their own abilities? Dunning and Kruger found that those at the high end of the competence spectrum did hold more realistic views of their own knowledge and capabilities. However, these experts actually tended to underestimate their own abilities relative to how others did.

Essentially, these top scoring individuals know that they are better than the average, but they are not convinced of just how superior their performance is compared to others. The problem in this case is not that experts don’t know how well-informed they are; it’s that they tend to believe that everyone else is knowledgeable as well.

Is There Any Way to Overcome the Dunning-Kruger Effect?

So is there anything that can minimize this phenomenon? Is there a point at which the incompetent actually recognize their own ineptitude? “We are all engines of misbelief,” Dunning has suggested. While we are all prone to experiencing the Dunning-Kruger effect, learning more about how the mind works and the mistakes we are all susceptible to might be one step toward correcting such patterns.

Dunning and Kruger suggest that as experience with a subject increases, confidence typically declines to more realistic levels. As people learn more about the topic of interest, they begin to recognize their own lack of knowledge and ability. Then as people gain more information and actually become experts on a topic, their confidence levels begin to improve once again.

So what can you do to gain a more realistic assessment of your own abilities in a particular area if you are not sure you can trust your own self-assessments?

- Keep learning and practicing. Instead of assuming you know all there is to know about a subject, keep digging deeper. Once you gain greater knowledge of a topic, the more likely you are to recognize how much there is still to learn. This can combat the tendency to assume you’re an expert, even if you’re not.

- Ask other people how you’re doing. Another effective strategy involves asking others for constructive criticism. While it can sometimes be difficult to hear, such feedback can provide valuable insights into how others perceive your abilities.

- Question what you know. Even as you learn more and get feedback, it can be easy to only pay attention to things that confirm what you think you already know. This is an example of another type of psychological bias known as the confirmation bias. In order to minimize this tendency, keep challenging your beliefs and expectations. Seek out information that challenges your ideas.

A Word From Verywell

The Dunning-Kruger effect is one of many cognitive biases that can affect your behaviors and decisions, from the mundane to the life-changing. While it may be easier to recognize the phenomenon in others, it is important to remember that it is something that impacts everyone. By understanding the underlying causes that contribute to this psychological bias, you might be better able to spot these tendencies in yourself and find ways to overcome them.

Functional fixedness is a type of cognitive bias that involves a tendency to see objects as only working in a particular way. For example, you might view a thumbtack as something that can only be used to hold paper to a corkboard